Integrating Google Colaboratory into Your Machine Learning Workflow

Are you using Jupyter notebooks regularly in your machine learning or data science projects? Did you know that you can work on notebooks inside a free cloud-based environment with a GPU accelerator? In this post, I will introduce you to Google Colaboratory and show you in a few simple steps how to integrate this platform into your daily workflow.

Jupyter notebooks are web-based interactive computational environments that have become a powerful and flexible tool to, e.g., teach computer and data science. Other use cases where you often might encounter Jupyter notebooks are machine learning or deep learning projects, which can be completed entirely from start to finish within a notebook environment. If you’re still unfamiliar with Jupyter notebooks or believe that a refresher would be in order, I would highly recommend you to check out these two tutorials by Alex Rogozhnikov and Benjamin Pryke, which give a broad overview of the capabilities of Jupyter notebooks and help you get started on building your first notebook.

In addition to the examples that I highlighted above, Jupyter notebooks have also become a popular interface to commercial cloud-based computing services. Google Colaboratory, or Colab for short, is a free cloud platform that you can access through a browser to work on notebooks. You might have encountered Google Colab before if you have recently been reading the TensorFlow documentation. According to the development team behind Colab, the goal of the project is to enable easier sharing of notebooks in a collaborative environment in an effort to advance machine learning education and research. When you use Google Colab, a GPU-accelerated virtual machine is fired up on demand as soon as you want to evaluate code in your notebook. The platform could, therefore, prove helpful in accelerating computational intensive parts of your projects, say if you’re normally working on a laptop without access to a more powerful machine.

I’ve decided to try out something new in this post which I’ve divided into two main sections. I’ll first discuss cloud-based computing services in a more general setting because I believe that we are heading towards a future where such services will play an increasingly important role. I will then present a short introduction to Google Colab, which should be more than sufficient to get you started on your first project on the platform. After reading this post, you should become familiar with the prospects of cloud computing services, and you should be able to decide whether Google Colab is an environment that could benefit you in your day-to-day workflow.

Cloud Computing: The Inevitable Future of Data Intensive Workflows?

Let me start off this post with a digression from today’s main topic by sharing with you my views on how compute-intensive fields of data science are evolving towards a computing-as-a-service model. This section is completely optional if you’re only interested in learning how to use Google Colab, though I would very much appreciate it if you decided to stick around. At the end of this section, I hope that I have succeeded in convincing you on the reasons why I believe data scientists, deep learning researchers, and machine learning engineers alike should get accustomed to Google Colab and other cloud-based services.

In many respects, we are in the midst of a paradigm shift in the way we use computers and computing resources for data science. As more and more data continues to become available to us, our demand for more powerful and faster computers keeps growing so that we are able to efficiently utilize the data to, e.g., make predictions or understand trends. At the same time, we want our personal machines to be light, portable, and have enough battery life to be able to survive through an 8-hour working day effortlessly. These are both aspects that high-performance cloud computing services can solve, and if you were to ask me, this is the inevitable outcome that we are headed towards in the future, at least in fields that require extensive computational resources especially if the demand is intermittent.

The simplest service cloud companies can offer is infrastructure. Very broadly speaking, this involves giving end users on-demand, over-the-Internet access to interconnected computer clusters and servers with dedicated storage and other auxiliary facilities. Nowadays, cloud computing services have evolved beyond infrastructural services as cloud companies have started diversifying towards more comprehensive platforms that offer tools and applications for a wider customer base, not just data science experts. For example, Google and Microsoft both currently provide a variety of tools ranging from productivity software (e.g. office software) to machine learning tools in their respective cloud application portfolios. Customer service and, in particular, software expertise are also services worth mentioning. To give you a broader overview of the cloud computing service model, I find this image from Wikipedia illustrates the main concepts rather well–I would strongly encourage you to check out the link to the main article if you want further information.

Hierarchical cloud computing service model. Image credit: Wikipedia.

The paradigm shift towards centralized computing is by no means a recent development. This a topic that is, in my opinion, best viewed from a historical perspective. The foundations of centralized computing can be dated back to the Manhattan project and the development of the first supercomputers. Although these supercomputers were very modest by modern standards (and aren’t usually even classified as supercomputers), their development was a momentous event that sparked the “computer age” in scientific research because these machines were successful in demonstrating that simulations could be a viable tool for research and development. Today, broad leaps in computing power and algorithms have cemented the role of numerical simulations in scientific research, e.g., within the field of chemistry. Reflecting back on my past four years as a Ph.D. candidate in this field, I am confident that the role computer simulations in research will continue growing in the upcoming decades–a trend that has largely been catalyzed by the rapid development of faster and faster supercomputers. The Top500 project website is an excellent source of information if want to learn more about where supercomputers and the field of high-performance computing are headed in the future.

Finland's current flagship supercomputer Sisu, which belongs to the Cray XC40 family. Image credit: Cray Inc.

Historically, the adoption of centralized computing services outside of academic and governmental research has not been as quick. I would argue that this is a classic case of a supply-and-demand problem: the majority of companies haven’t seen a demand for more computing infrastructure or other cloud-based services, so the number of companies offering such services has remained limited. Those companies that were the rare exceptions and required more resources than local workstations could offer usually had to resort to on-site operated computer clusters. The ongoing artificial intelligence and machine learning boom has awakened companies to the prospects of computer modeling and data science. The growing demand for commercial cloud-based services has, in turn, attracted a large array of companies to the market, which have skyrocketed in numbers since the mid-2000s when Amazon introduced their EC2 platform.

I view this trend towards the greater use of cloud-based services as beneficial both from the vantage point of companies and private individuals, the collective “end users”. Buying, operating, and maintaining computing infrastructure (hardware and software) is expensive in terms of acquisition and labor costs. In a cloud computing setting, these costs are shared among all end users which brings down the total cost on an average basis. Cloud providers naturally take a cut from the operating income as profit, as they are fully entitled to do. The competition between peers should help prevent cost escalation and ultimately spur the development of better cloud services and platforms. Another benefit of cloud computing platforms is the fact that they make machine learning and other data science techniques more accessible to everyone because you no longer need to own your own machine or be a software guru in order to efficiently use the computational tools. The growth and diversification of the userbase will also lead to new exciting method applications, which will help guide software development in the future. As the cloud computing scene matures, it will be interesting to see what kind of balance will be reached between the use of commercial and open source software.

Google Colaboratory–a cloud-based environment for Jupyter notebooks.

Getting Started with Google Colaboratory

I hope that my discussion in the preceding section has managed to convince you why learning to use cloud-based tools is worth your time. We are now ready to move on to the main topic of this post, namely, how to use Google Colab as an interactive cloud-based Jupyter notebook environment.

Getting started with Google Colab is very simple: the front-page itself is an introductory notebook that will familiarize you with the platform. You can access a couple of additional tutorials by selecting File > Open > Examples. Evaluating code inside notebooks does not cost anything when you use Google Colab, and only requires you to sign in with your Google account. Behind the scenes, Google Colab is a non-persistent virtual machine hosted on Google Cloud, which is something you should keep in mind when using the platform as I’ll explain shortly. Numerical computations in Google Colab can be accelerated using a GPU backend on supported machine learning frameworks, again without incurring any cost. This a very appealing option if you’re like me and regularly work on a laptop without access to a machine with a dedicated GPU and you want to, e.g., reduce the training time of a TensorFlow model that you’re building.

Once you’re done with the introductory Colab tutorials, you can continue to explore the platform by opening an example notebook from the Colab-powered Seedbank database, which contains notebooks that cover a wide range of machine learning topics. Alternatively, you may start working on your own notebook either by creating from one scratch or by importing an existing one into Colab. You have three choices on how you can import a notebook if you select the File > Open dialog:

Option 1. You can import a notebook directly from GitHub by searching notebooks on a per-user and per-repository basis. You have another option if you know the URL to a GitHub-hosted notebook. You can simply strip the https://www. part from the GitHub URL and prepend it with colab.research.google.com/ to open up the notebook directly. I’ve included an example link below to a notebook that I prepared specifically for this post, which you’re more than welcome to check out. I adapted the notebook from one of the exercise notebooks that are a part of the Stanford University convolutional neural networks class by making the notebook Google Colab compatible.

Option 2. Import a notebook from Google Drive.

Option 3. Upload a local file from your computer.

I mentioned earlier that the allocated computing resources are non-persistent when you use the Google Colab notebook environment. This means that you will permanently lose any unsaved work once the resource allocation expires (12 hours). Don’t worry, saving your notebook or your trained machine learning model are both straightforward once you get the hang of things. The notebook is the simplest thing to save: just hit the save button and a copy of the notebook will be stored in a new folder on your Google Drive. Exporting the notebook to GitHub as a commit (you must first grant Google Colab the privileges to do so) or downloading it to your computer are alternative options that you can select from the File dialog.

Saving a trained model or outputting any other data takes a couple of extra steps. You again have a couple of choices on how you can save the data. Note that these same instructions also work in case you want to import data or a model into the Google Colab environment.

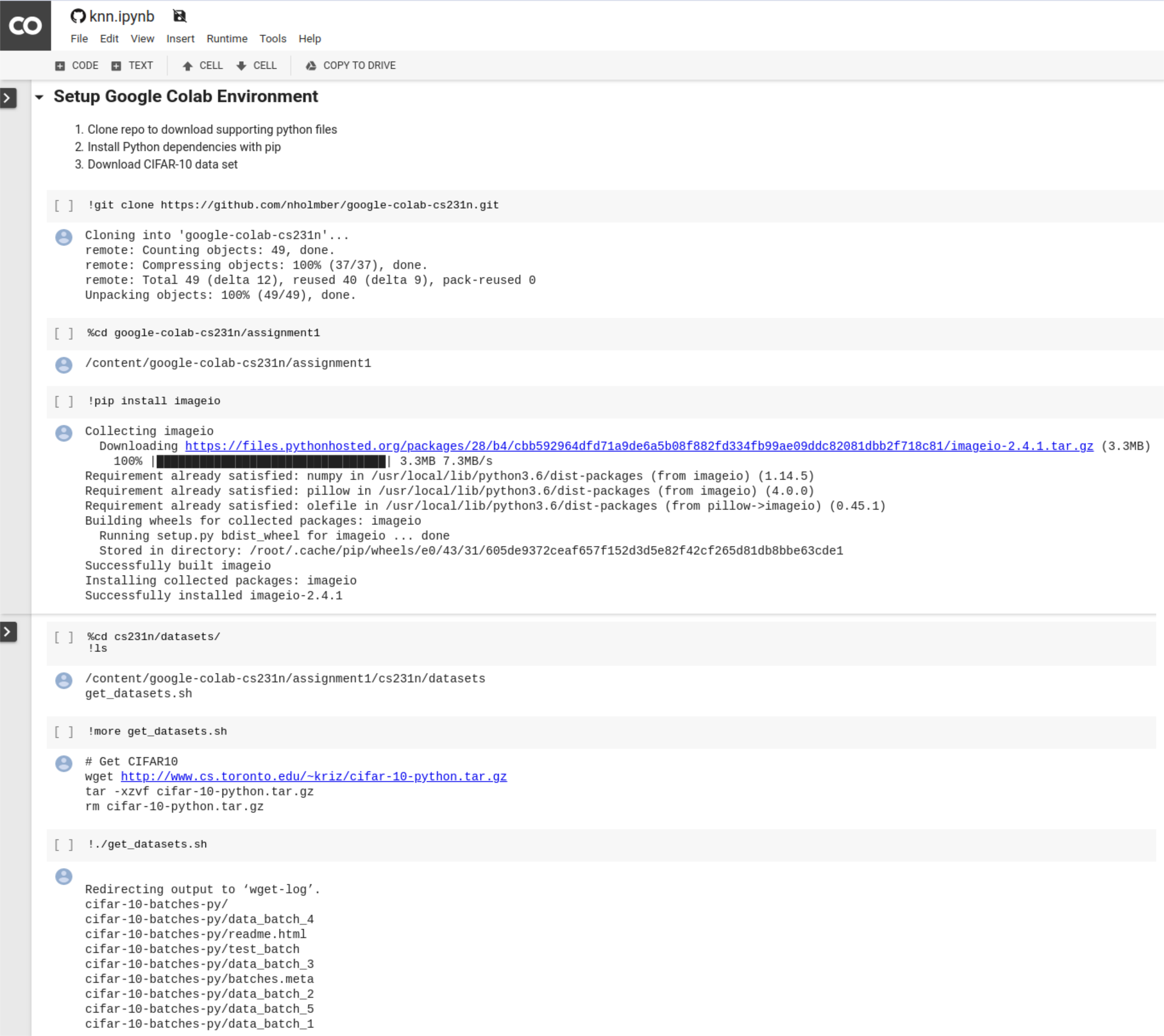

Option 1. You have access to the command line in a Jupyter notebook. You can use the command line to clone a git repository in order to push or pull data from a remote repository. Here’s an example how you can pull Python dependencies and input data into a Google Colab notebook.

Option 2. As an alternative to a remote git repository, you can mount Google Drive as a folder that you can access for storing and retrieving data. You can follow the instructions in this post if you are interested in this option.

Option 3. You can upload or download files directly from or to your computer with Python. You can find the instructions in this tutorial notebook, which also discusses some alternative options in addition to the options 1-3 that I have introduced here.

Further Reading

You should now be ready to use Google Colab in your own projects. I’ve intentionally kept the tutorial portion of my post quite compact because, at the end of the day, using the environment is meant to be relatively easy and unobtrusive. The actual challenge is, of course, creating the notebook that you need to complete your project. If you nevertheless feel that this post was too brief and did not cover Google Colab adequately enough, you might find the following articles worth reading

Congratulations, you’ve reached the end of this post. As I mentioned earlier, I decided to test something new in this post by first introducing cloud computing services as broader background to Google Colab, followed by a short how-to tutorial. What did you think about this approach? Would you have preferred two separate posts with more substance in each? I’d love to read your comments and your thoughts on cloud computing.